What was it about The Ring Nebula (M57) that inspired me to put together this little blog article? I guess it must be that it was the first telescopic ‘deep-sky object’ that I ever learned how to find and observe . (I didn’t call them deep-sky objects back then and the brighter wonders such as the Andromeda Galaxy and the Orion Nebula which are visible to the naked eye don’t count! ) I remember using my 60mm Tasco refractor back in 1971, as an 11 year old to look at this lovely object, and was amazed by it. Within a few months I would see it in Patrick Moore’s 12″ Newtonian Reflector – well what can one say – incredible!

It was always likely to be M57 (out of many other objects) because it is really easy to find, located as it is between two stars in the ‘parallelogram’ of Lyra the lyre. Also, Lyra itself is easy to find because of its brightest star Vega, and the fact that Lyra is a compact constellation right next to it.

Before we go zooming in on M57, what exactly is it? It is a planetary nebula, so called because, at first glance, it presents a planet-like disk to an observer through the telescope. However, instead of being at Solar System distances, it is roughly 2,500 light-years away and was formed when a dying red-giant star blew out its outer layers before becoming a white dwarf. Such a fate will probably befall our own Sun in about 5 billion years! Now, we see the remaining shell of ionised gas as it expands into the interstellar medium.

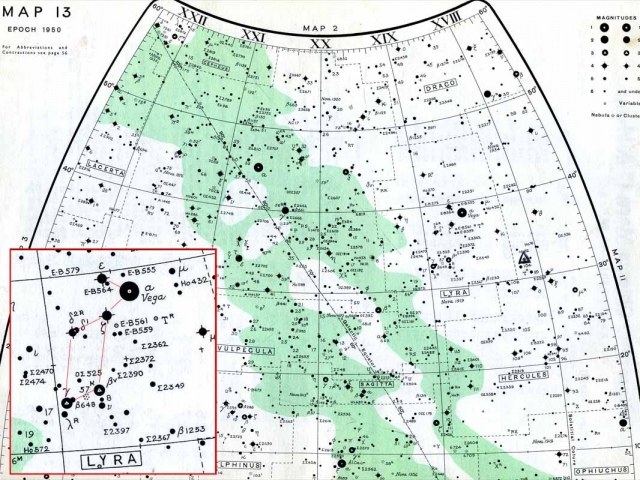

So, the idea behind this blog is to locate M57, and zoom into it using images that go from wide-angle camera shots to high resolution images from large telescopes. First, I’ll transport you back to my world of the early 1970’s by showing this scan from the wonderful star maps at the back of the classic Norton’s Star Atlas. I still reach for this book when I need to remind myself of various bits of the night sky! Here is the scan, I added the insert showing Lyra at a larger scale, but the map itself in very evocative to me, covered with the rubbed-out tracks of pencil-drawn trails from long-gone Perseid or April Lyrid meteors. You will see M57 indicated between the stars β (Beta) and γ (Gamma) Lyrae at the bottom of the parallelogram shape (which I have outlined).

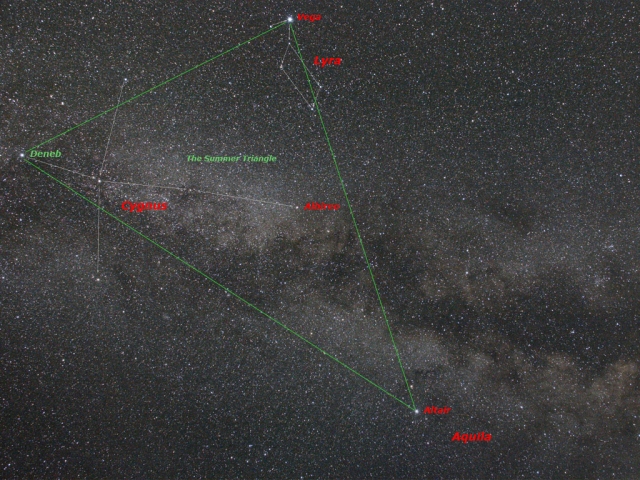

Now, on to the first image. I took this back in early June this year using a Canon DSLR camera and an 18mm lens, giving a nice wide field view. (as with all these images – click on them to see them at full size, then click again to return). I have indicated a large green triangle which is known as The Summer Triangle consisting of the 3 bright stars Vega, Deneb and Altair. I have also annotated the cross shape of the constellation of Cygnus the Swan which is getting rather swamped by the Milky Way in this picture. You can see Lyra near the top.

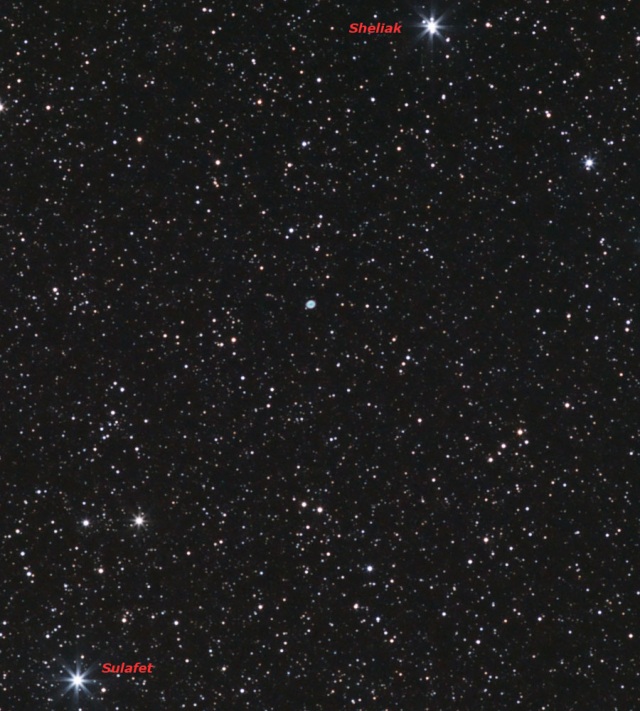

The next image is only a bit more of a close up Lyra, taken with a 28mm lens this time. I have added the names of the two stars that straddle either side of the ring nebula. As you can see Beta Lyrae has the proper name of Sheliak, and Gamma is called Sulafat. Also annotated are a few of the other brighter stars in this field – Albireo is the head (or beak) star in the cross of the Swan. Many of the proper names of stars in use today come from an Arabic origin and Sulafat comes from the Arabic for ‘turtle’ or ‘tortoise’ as it seems that most fine harps (or lyres) were decorated in tortoiseshell.

So, let’s zoom in a bit further. Next I changed to a 50mm lens and have also added an insert to this image. The insert is at the full resolution of the image whereas the rest of the picture has been much reduced in size to get it on this page. Now we can actually see the Ring Nebula! It’s pretty small as you can see, in fact it is approximately 3.5′ (arc-minutes) across which is, roughly speaking, only one tenth the apparent diameter of the Moon. Note the use of the word ‘apparent’ there; The true size of M57 is some 3 light-years across!

Now the last camera shot, before moving to a ‘proper’ telescope (telephoto lenses are telescopes really, but you get the idea). This time, I used a 200mm lens and I have cropped out the Sheliak/Sulafet region. Now we can see the ring and can understand why this is known as a planetary nebula. It certainly confused its discoverer. French astronomer Antoine Darquier de Pellepoix in January 1779, reported that it was “…as large as Jupiter and resembles a planet which is fading.” This is a good description as Jupiter is typically about 45′ across, but much brighter of course! Another Frenchman, Charles Messier, independently found the same nebula later on in the same month while searching for comets. He entered into his famous catalogue as the 57th object (Note that the main reason for Messier’s famous list was so that he would remember these ‘fuzzy’ objects and not confuse them with Comets which were his main interest).

The following image was taken with my Celestron C11 telescope and an ATIK 383L cooled CCD camera. I used a filter called an H-Alpha filter which passes light in a very narrowband of frequencies. I was after the outer shell of M57 – something I had never really seen in older photographs, but nowadays it is commonly captured by amateur astronomers using sensitive CCDs. It does require long exposures to bring the faint outer shell out, and I stacked together several 20 minute exposures to reveal it here.

The previous, rather noisy, image is certainly not my finest moment! I really don’t have a good telescopic image of M57. So to finish this article with a splendid image, I asked Robert Gendler if I might use one of his (for those of you who don’t know, Robert is one of, if not the best deep-sky imagers and image processors in the world) . He kindly suggested that I use this incredible image of M57. For more information about this particular image, and about M57 in general see Robert’s page here:

http://www.robgendlerastropics.com/M57-HST-Subaru.html

That’s it for my take on M57. Maybe I’ll make the Zoom into theme a regular feature here, so watch this space!